The Tsilhqotin and Xeni Gwetin Court Case for Rights and Title

April 18, 1990, the “Nemiah Trapline Action”, was brought by the plaintiff Chief Roger William in his capacity as Xeni Gwet'in Chief, on behalf of all Xeni Gwet'in and all Tsilhqot'in people, in the Supreme Court of B.C. vs. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of the Province of British Columbia, the Regional Manager of the Cariboo Forest Region and the Attorney General of Canada. The case was heard by Justice David Vickers.December 18, 1998, the “Brittany Triangle (Tachelach’ed) Action” began.

Both actions were provoked by proposed forestry activities in Tachelach'ed and the trapline territory.

The area claimed is approximately 4,380 sq. km or 438,000 ha.

November 18, 2002, the trial commenced in Victoria, B.C. A total of 339 days of testimony were heard until the trial ended on April 7, 2007. During the fall and winter of 2003, the Court sat for 5 weeks at the Naghatanequed Elementary School in the Nemiah Valley.

In the course of this lengthy trial, the court heard oral history and oral tradition evidence and considered a vast number of historical documents. Evidence was tendered in the fields of archeology, anthropology, history, cartography, hydrology, wildlife ecology, ethnoecology, ethnobotany, biology, linguistics, forestry and forest ecology.

November 20, 2007, Justice Vickers ruled that the Tsilhqot'in people are a distinct Aboriginal group who have occupied the Claim Area for over 200 years.

November 20, 2007, Justice Vickers ruled that the Tsilhqot'in people are a distinct Aboriginal group who have occupied the Claim Area for over 200 years.The court dismissed the claim for a declaration of Aboriginal title to the claimed area, relating to the "all or nothing" way the claim was pleaded. It did, however, express its opinion that the Tsilhqot'in Nation had proven Aboriginal title to parts of its claimed traditional territory.

In summary, the Court found:

1. The Tsilhqot’in people have aboriginal rights, including the right to trade furs to obtain a moderate livelihood, throughout the Claim Area.

2. British Columbia's Forest Act does not apply within Aboriginal title lands.

3. British Columbia has infringed the Aboriginal rights and title of the Tsilhqot’in people, and has no justification for doing so.

4. Canada’s Parliament has unacceptably denied and avoided its constitutional responsibility to protect Aboriginal lands and Aboriginal rights, pursuant to s. 91(24) of the Constitution.

5. British Columbia has apparently been violating Aboriginal title in an unconstitutional and therefore illegal fashion ever since it joined Canada in 1871.

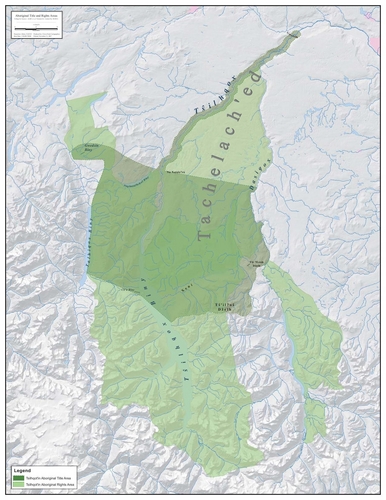

(The dark green in the map above shows the area where Justice Vickers said the Xeni Gwet'in had proven their title case - approx. 50% of the claim area - and the light green, their proven rights area. Fish Lake, the area of Taseko Mine's proposed "New Prosperity" Mine is within the proven rights area.)

All parties to the litigation appealed this decision.

November 15-22, 2010, the appeal case was heard in the British Columbia Court of Appeal.

June 2012, the B.C. Appeal Court upheld the rights judgement of 2007 to hunt, trap and trade in their traditional territory but said that title could be claimed only to areas that were specifically occupied or used "intensively" and not to the broad lands between those areas that, to a "semi-nomadic" people, are integral to those very hunting, trapping and gathering rights. This is the "postage stamp" approach to aboriginal title that the William case opposes. The Tsilhqot'in appeal this decsion.

January 2013: The Supreme Court of Canada will hear the Tsilhqot'in Title Case.

Synopsis: In the original "William case" for rights and title in 2007, Judge Vickers ruled that the Tsilhqot'in people had proven rights to the territory claimed in court and also a right to claim title to a large part of that land, including the Nemiah Valley; citing a technicality, he stopped short of granting title. This ruling was appealed by both levels of government and plaintiff, Roger William (i.e. Roger William, on his own behalf and on behalf of all other members of the Xeni Gwet'in First Nations Government and on behalf of all other members of the Tsilhqot'in Nation). After hearing this case, in 2012 the B.C. Appeal Court upheld the rights judgement of 2007 to hunt, trap and trade in their traditional territory but said that title could be claimed only to areas that were specifically occupied or used "intensively" and not to the broad lands between those areas that, to a "semi-nomadic" people, are integral to those very hunting, trapping and gathering rights. This is the "postage stamp" approach to aboriginal title that the William case opposes.

“For us, the Court of Appeal denied the legitimacy of our laws, our ways of life, who we are as Tsilhqot’in people,” said Chief Joe Alphonse, Tribal Chair and Chief of Tl’etinqox-t’in community, “We’re grateful to have the opportunity to present to the Supreme Court of Canada a different path to reconciliation. And we are honoured to stand with the support of First Nations across British Columbia and Canada. Together, our voices will be heard at last”.

This is likely the most important aboriginal land claims case since the Delgamuukw decision in 1997. That decision recognized that such a thing as aboriginal title existed and continues to exist in theory but did not declare that the Gitxsan and Wet'suwet'en peoples had title to their claimed territory in that case. In the intervening 18 years there has been no recognition of what First Nations have been asserting all along, the recognition aboriginal title on the ground.

“We never gave up our rights or title and further proved our Aboriginal rights and stopped forestry in that critical part of our homeland. That is something to celebrate,” said Marilyn Baptiste, Chief of Xeni Gwet’in. “But this is not complete for our people. At the Supreme Court, we will continue to tackle the most important issue for us and for ALL First Nations – our Aboriginal title to the land”.

The importance of the William case cannot be overestimated as it raises one of the most central issues of indigenous rights that exist in Canada: what land rights do First Nations hold today over the lands they controlled before the Crown asserted sovereignty? The way this question is answered will determine the place of First Nations in Canadian society, the extent to which they will control their own future and the shape of Crown-First Nations relations for decades to come.

“We are truly grateful for the many Tsilhqot’in Elders that showed the courage to share their knowledge at trial, in our Tsilhqot’in language,” said Councillor Roger William, the plaintiff in the case, “Many of them are no longer with us today. They would be proud and honoured to know that their case will be heard by the highest court in Canada.”

It is expected that this case could take a year to get to trial.

November 7, 2013:

In an amazing feat of organization and fundraising, a busload of Tsilhqot'in people set off on an epic “Journey for Justice” from Williams Lake to Ottawa on October 30th. On board were some of the remaining elders who testified at the original case for rights and title before Justice Vickers, some youth, leaders, staff and other community members. Their journey, also dubbed the “Indigenous Land Title Express” stopped at other Aboriginal communities across the country, sharing stories, information and ceremonies and, in a show of solidarity with the Tsilhqot'in people, these communities also did significant fund-raising in support of the journey.

The case is heard before the Supreme Court of Canada. The only issue to be decided is Aboriginal title as neither the federal nor provincial governments appealed the original 2007 decision re proven rights.

In the words of David Rosenberg, Q.C., Counsellor for the Appellent:

"The Tsilhqot’in people have fought for recognition of their fundamental rights as the original possessors of their traditional lands for generations. In the Chilcotin War, their Chiefs literally gave their lives in defence of their territory in the face of a hostile colonial government and an unsympathetic court system. Although this betrayal lives on today, vividly, in the hearts of the Tsilhqot’in, the Tsilhqot’in people have invested over 20 years in the Canadian court system. They have done so with a singular hope: that the courts will deliver on the promise of s. 35 and recognize and affirm their Aboriginal title to the land, undiminished by discrimination or political expedience, so that the real work of reconciliation can finally begin.

"To this day.....over 15 years since Delgamuukw, Aboriginal title exists only as an abstract legal theory in Canada, with no practical recognition or meaning on the ground. The time for recognition of Aboriginal title is now, not only because it is long overdue and urgently needed, but because the governing law and the facts of this case call for it. The Trial Judge properly applied the law of Aboriginal title as articulated by this Court. His understanding of the facts was comprehensive, his findings undisputed on all significant matters. In the result, he found Aboriginal title was proven on the evidence to some – but not even half – of the Claim Area, lands that “provided security and continuity for Tsilhqot'in people”. In the words of the Trial Judge, the Appellant submits that “the time to reach an honourable resolution and reconciliation is with us today.”

June 26, 2014: A win!!!! The Supreme Court of Canada issues a historic ruling of Aboriginal title to the Tsilhqot'in people.

"Held: The appeal should be allowed and a declaration of Aboriginal title over the area requested should be granted. A declaration that British Columbia breached its duty to consult owed to the Tsilhqot’in Nation should also be granted".

On June 26, 2014, the Supreme Court of Canada released a unanimous 8-0 decision acknowledging the truth of what the Xeni Gwet'in peoples of the Tsilhqot'in have always known: they do have title to their traditional territory. Building on the groundbreaking ruling by Justice David Vickers in 2007, the SCC granted Aboriginal title to 1,750 sq. km., thereby firmly and finally denying the narrow "postage stamp" view of title that was under appeal. The Supreme Court ruled that "occupation sufficient to ground Aboriginal title is not confined to specific sites of settlement but extends to tracts of land that were regularly used for hunting, fishing or otherwise exploiting resources and over which the group exercised effective control at the time of assertion of European sovereignty." This ruling marks the first time the Supreme Court has recognized Aboriginal title to a specific piece of land.

"This decision means we now have the opportunity to settle, once and for all, the so-called 'Indian land q

uestion' in B.C. and elsewhere in Canada where Aboriginal title exists through good faith negotiations," Assembly of First Nations Regional Chief of B. C. Jody Wilson-Raybould said.

uestion' in B.C. and elsewhere in Canada where Aboriginal title exists through good faith negotiations," Assembly of First Nations Regional Chief of B. C. Jody Wilson-Raybould said.“We take this time to join hands and celebrate a new relationship with Canada. We are reminded of our elders who are no longer with us. First and foremost we need to say sechanalyagh (thank you) to our Tsilhqot’in Elders, many of whom testified courageously in the courts. We are completing this journey for them and our youth. Our strength comes from those who surround us, those who celebrate with us, those who drum with us” said Plaintiff, Chief Roger William of Xeni Gwet’in.

This ruling of Aboriginal title confers rights including:

- the right to decide how the land will be used;

- the right to economic benefit of the land;

- the right to pro-actively use and manage the land.

"The right to control the land conferred by Aboriginal title means that governments and others

seeking to use the land must obtain the consent of the Aboriginal title holders". If consent is not provided, "the government's only recourse is to establish that the proposed incursion on the land is justified under s.35 of the Constitution Act, 1982".

seeking to use the land must obtain the consent of the Aboriginal title holders". If consent is not provided, "the government's only recourse is to establish that the proposed incursion on the land is justified under s.35 of the Constitution Act, 1982".Furthermore, the SCC found that the B.C. Forest Act does not apply to to the Tsilhqot'in Aboriginal title lands so that the beneficial interest in the land, including its resources, belong to the Tsilhqot'in title holders.

FONV honours the perseverence and courage of the Xeni Gwet'in First Nations and all the Tsilhqot'in people whose truth has finally been recognized by Canada. This is a historic day for First Nations and for all Canadians as we move from a pattern of denial of FNs rights into a readiness to reconcile through acknowledgment, in real ways, of those those rights.

Tsilhqot'in Nation v. British Columbia, 2007 BCSC 1700

Victoria, British Columbia, November 21, 2007 - After a courageous and epic struggle, a small Tsilhqot'in First Nation that took on the governments of Canada and British Columbia to protect their land and way of life has been victorious in Court. In a major precedent-setting decision, Justice David Vickers of the British Columbia Supreme Court ruled today that the Tsilhqot'in (Chilcotin) people have proven Aboriginal title to approximately 200,000 square hectares in and around the remote Nemiah Valley, south and west of Williams Lake, British Columbia. Although Justice Vickers declined to make a declaration of title based on technical issues, he found that the tests for evidence of title were met in almost half the area claimed.

The trial lasted 339 days during which 29 Tsilhqot’in witnesses gave evidence, many in their native language. 604 exhibits were entered with Exhibit 156 alone containing over 1,000 historical documents. The Judge received about 7,000 pages of written submissions from the lawyers on all sides.

"The court has given us greater control of our lands. From now on, nobody will come into our territory to log or mine or explore for oil and gas, without seeking our agreement," said the Plaintiff, Chief Roger William. "The court recognized that we have proven title in about half of the Claim Area - and from today we accept our renewed responsibility and powers of ownership of those lands."

Throughout much of Canada and the United States, the colonial governments made treaties with First Nations to purchase their lands. This did not happen in most of British Columbia. The government has continued to deny that B.C.'s indigenous people inherited the land that their grandparents owned.The Xeni Gwet'in claimed roughly 440,000 hectares as their traditional territory in a lawsuit that started as a battle against large-scale commercial logging. It is expected Judge Vickers will find the band established exclusive and continuous occupation - the current legal test of title - to nearly half of that parcel of land.

That's far more than the Crown has been willing to put on the table in negotiations. Modern treaties in British Columbia have averaged about 5 per cent of the traditional territories claimed, although they also include cash compensation.

Both the federal and provincial governments opposed the band's broad claims but made unprecedented concessions. The Crown accepted the band's claims to aboriginal rights to hunt and fish in the valley, and conceded title in a very limited way.

"This is an absolutely critical decision and it may have significant ramifications for treaty negotiations," Shawn Atleo, B.C. Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, said in an interview yesterday."